Designing Microscopy Experiments Related To Infectious Diseases And Antivirals

Designing microscopy experiments related to infectious diseases and antivirals can be challenging, but there’s never been a more vital time than right now to design adequate microscopy experiments. The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and spread across the globe becoming the pandemic that the world is reeling with today. Currently, COVID-19 has no targeted therapies approved by the FDA, so the best coronavirus prevention happens through social distancing and good hygiene practices. However, companies are rapidly testing candidate molecules and vaccines as fast as they can. Initial tests suggest there may be some drugs that could be repurposed for COVID-19 treatment. Repurposed drugs have already shown their safety, so clinical trials need to be conducted for effectiveness only.

SARS-CoV2 belongs to a family of viruses that we’ve encountered before, so there is hope that we can apply the knowledge we have about SARS and MERS for treatment. Looking towards the future, since 75% of emerging infections have come from animals (zoonosis) we will continue to see new pathogens in our lifetimes. What does the research & development pipeline look like for combating these new infectious diseases?

In 2013, I worked for a company called Evrys that works on host-directed antivirals. Drugs like these are special because the therapeutic target is our cells instead of the virus directly. There are different pathways towards a successful drug, but this outline should be applicable to many research and development (R&D) workflows. Here, we will go over the steps that R&D takes to develop new treatments and how microscopy assists with the research.

1. Determine a druggable target.

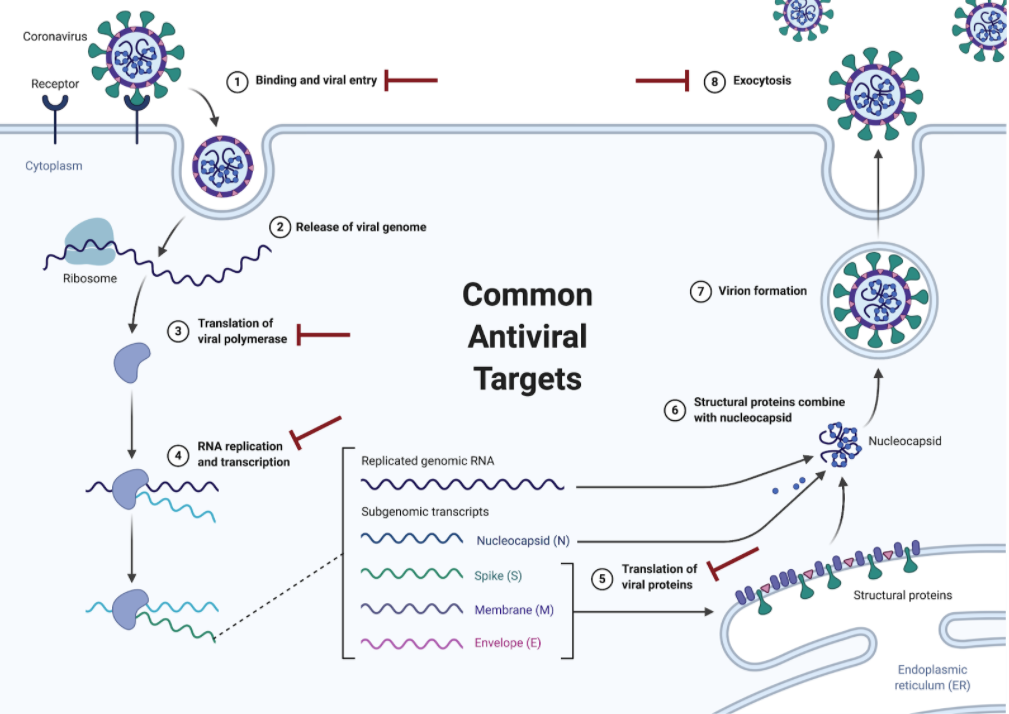

Viruses can be grouped into a major class even if they are new. All coronaviruses (including SARS-CoV & MERS-CoV) are enveloped positive-sense RNA viruses that have club-like spikes on their surface and similar life cycle steps, allowing for prior knowledge of similar viruses to be used. If we encounter a new virus, sequencing the genome and obtaining electron microscopy images is the best place to start to determine what type of virus we are dealing with. Common antiviral targets interfere with receptor binding, membrane fusion/entry, replication, protein translation, and viral release. While writing this, Clinicaltrails.gov listed 112 active clinical trials for COVID-19 treatment. Current targets include RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (remdesivir, favipiravir) and viral entry (Baricitinib, ACE inhibitors). Knowing the target can help narrow down the compounds used in the primary screen, but it is not necessary due to the simple readout of “virus” or “no virus.”

2. Primary Screens

Primary screens are when scientists test compounds (numbering from 1K to 10K) for antiviral activity. The “effective concentration” is the concentration of product at which virus replication is inhibited by 50%, e.g. EC50 for cell-based assays and IC50 for biochemical or subcellular assays.

The most common microscopy technique used in this stage of drug development is high throughput screening (HTS). There are a variety of microscopes that are capable of HTS, but they all share similar features. These microscopes accept 96-well to 1536-well plates and automatically image all the wells for the users.

Ideally, specific antibodies have been produced at this point to allow for fluorescence microscopy.

This entails using widefield or confocal microscopes to observe a decrease in viral load, as well as cytopathic effects (structural cell changes). Cytopathic effects can often be seen using phase contrast or DIC microscopy. For more information on determining the health of your cells, check out our 6 Microscopy Assays To Determine Cell Health and Improve Your Experimental Results blog.

3. Secondary Screens

Once a potential drug has been identified, it is important to ensure that there are not any unintended side effects on healthy cells. The goal is to stop viral replication without killing the uninfected cells. This work again uses a HCS microscope. It tests a series of increasing concentrations of the possible drugs to determine the concentration at which the compound kills 50% of the cells (known as CC50 value). The concentration for which the compound kills 50% of the cell in culture is divided by the concentration needed to kill 50% of the virus, giving us a therapeutic index. The therapeutic index is important because it provides the difference in concentration between when it is helpful and when it could be toxic to the patient. Many over the counter drugs such as Claritin (loratadine) have a high therapeutic index and thus it’s difficult for a patient to overdose. The drugs that have the best therapeutic index will undergo further optimization with chemists making many small changes. And you guessed it, more cellular assays on HCS microscope to ensure safety.

4. Antiviral Activity in Vivo

A lot of good information can come from in vitro studies, but they can’t replicate the effects observed in a whole organism. This is where in vivo studies become useful. In vivo studies generally rely on developing an animal model of the infection and treating it with possible drugs. Work on coronavirus is currently being performed using a specialized mouse that has the human ACE2 receptor.

Animal studies study the effect of the drug on a whole-body level. The main goal is to determine important information for regulatory agencies such as dosage, toxicity, and/or carcinogenicity. For a more complete list of parameters check here. During the course of the in vivo study, researchers measure parameters such as weight and temperature regularly. After the animal dies, researchers use brightfield microscopy and histological staining of tissues and blood to determine any toxic or carcinogenic damage that has occurred due to treatment.

The most basic of the assays is staining tissue sections from different organs with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Animal studies for coronavirus would obviously examine the lungs, but it is also important to examine any histopathological changes in the gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidneys, heart, thyroid, and brain. Drug side effects occur when there are off-target effects in the cells. Although anyone can perform the histology sample preparation and imaging, someone with proper pathology training should analyze the samples. Imaging can be done using any brightfield microscope, but drug development companies have moved to use slide scanners. Slide scanners are digital microscopes that image the entire slide (or specified region) and can image 100s of slides each day. Not only do slide scanners allow high throughput imaging, but they can achieve incredible reproducibility.

Other microscope assays that are important in the in vivo stage are blood smears and apoptosis assays. Blood smears are paired with histological dyes to examine changes in red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Changes in these blood components can be an indicator of more serious systemic changes. Finally, apoptosis assays are important to determine any cellular death caused by the antiviral. There are a variety of different ways to measure apoptosis, but in tissue sections, TUNEL assays are the preferred method due to the simplicity and the ability to perform the assay in a high throughput manner.

Microscopes are necessary at several stages of the research and development of antivirals. Time is very valuable, especially with the current pandemic, so learning to use high throughput machines is key to being successful. Although many of the features are automated, it is important to know enough about the microscope and the biology to ensure biologically relevant data are obtained. Just like in normal microscopy, don’t forget the proper controls! You don’t want thousands of pictures that are of no use to you or even worse, follow an incorrect lead during development.

To learn more about important control measures for your flow cytometry lab, and to get access to all of our advanced materials including 20 training videos, presentations, workbooks, and private group membership, get on the Flow Cytometry Mastery Class wait list.

ABOUT HEATHER BROWN-HARDING

Heather Brown-Harding, PhD, is currently the assistant director of Wake Forest Microscopy and graduate teaching faculty.She also maintains a small research group that works on imaging of host-pathogen interactions. Heather is passionate about making science accessible to everyone.High-quality research shouldn’t be exclusive to elite institutions or made incomprehensible by unnecessary jargon. She created the modules for Excite Microscopy with this mission.

In her free time, she enjoys playing with her cat & dog, trying out new craft ciders and painting.You can find her on twitter (@microscopyEd) a few times of day discussing new imaging techniques with peers.

More Written by Heather Brown-Harding