Ask These 7 Questions Before Purchasing A Flow Cytometer

Using funds to make a capital purchase can be an exciting time in a facility. If you don’t have the funds in hand, planning for future purchases requires due diligence to make sure the investment is worth it, and that it will satisfy the needs of the community. That $200,000 or more (sometimes much more) is an investment in the future research capabilities of the facility, so invest wisely. Over the course of writing instrumentation grants, developing business plans, and acquiring instruments, the following questions should be your go-to checklist — what I look at and what you need answered before spending that hard-won funding.

1. What role does the instrument need to fill?

At the top of the questions list is identifying the instrument’s role. What does the research community need at the moment, and in the near future? Develop good tracking metrics on current trends in usage, and ask major users about their 1-to-3-year plans. And, don’t forget to investigate funding status.

Your data may suggest you need another cell sorter, but as you investigate grant situations, it may be clear that the group(s) dominating the sort time may be changing their focus. They may not even have the funds to maintain work at the current level. Other researchers may need a different instrument.

Figure 1: Questions to gauge community needs.

Consider also any similarities and differences to currently available technology. One thing to investigate is the possibility of partnership with another regional facility. If that facility has access to the instrument(s) you need, then a brand new purchase may not be necessary. The benefit of this plan is that focus could be turned instead to other technology in order to expand services.

As an example, take the CyTOF mass cytometer: perhaps you have two or three investigators who are very eager to acquire the instrument, but the majority of the researchers need additional sorting. Since CyTOF samples are fixed, and there is extensive data on the stability of these samples, it is possible to partner with another institution and gain access to their system without bringing one in-house, thus granting access to the needed sorter.

2. How much space do you have?

The second of the questions you should ask is you want to look at is the space in your facility. Some of these instruments are large. If you’ve ever seen an LSR 2, you know it’s enormous. Some newer generations of instruments are getting so small they can fit into unbelievably tiny spaces. This means you can easily incorporate them into your laboratory. So, always remember to look at the potential storage spaces within your facility.

Figure 2: Dimensions from some common flow cytometers. (Data from vendor websites)

3. What’s your budget?

The next consideration is questions regarding your budget. It is critical to consider more than just the purchase price at this time. The other considerations must include any renovation costs required for placing the new instrument, because you may want to renovate existing space to make it suitable for the operation of the instrument. This might even cost around $100,000. Ask the vendor for the site installation guide and partner with your local facilities teams. These steps will help you see how well the room can support any requirements.

This is also the time to look at the operating budget for the new system. Will new personnel be needed to operate the system? Are there specialized items needed for the system? Will the system be under service contract after the first year and, if so, how much does that cost? Will refresh rates cover the costs? These questions will lead you to the annual costs that need to be covered.

Speaking of service contracts, make sure that you know what’s covered under yours. Be very clear on what is covered and what is a consumable. Are software upgrades part of the service contract? What about when operating systems change? (Remember when Microsoft stopped supporting Windows XP?) Lest you make a mistake to the tune of $10,000 per year, remember that the fine print is critical.

4. Meet the service team.

Speaking of service contracts, learn about the people who will be providing services and support. Here are a few questions to ask them. How far away are the closest service engineers? What is their response time? Not just for service to arrive at your facility, but for spare parts in the event of repairs.

Over the years, building a positive relationship with the service team is an invaluable asset. That team can help you learn to diagnose (and even repair) smaller issues to keep your system up, which in turn makes the researchers happy.

It’s a two-way street: as you get to know your service engineer, they will get to know you. If they have a clear appreciation for your own skill level, they can help walk you through steps that give them additional insights about any instrument issues. Then, they can either guide you through a simple fix, a work-around to keep the cells flowing, or have the parts ordered so that there’s no delay when the goods arrive on site.

I am still convinced that my first cell sorter was possessed. The number of issues that I had with that system remains hard for me to believe, even after all these years. My service engineer and I actually became friends and bonded over this sub-par system. I gained invaluable insight into the workings of the system and improved my troubleshooting skills. I became so competent that eventually, when I called him for help, he knew it was a significant issue, and that I had done all the early troubleshooting and finally reached a point where it was time to call the pro.

Figure 3: The insides of a flow cytometer (image from UCFlow blog)

5. Can you organize a demo in your lab?

Would you purchase a car without test-driving it? The same can be asked of a researcher purchasing a new instrument. It’s critical to watch the system operate right there in front of you. Marketing material is all well and good, but the important thing is to see how the system really works.

Ideally, you can arrange a demo in your facility. Get samples from the researchers and compare the data to current instruments. Find the hardest samples and put them on the instrument.

If you can’t have a system in your facility, make sure to visit a site that is running the system and arrange to bring samples.

Also, get names of users who are currently working with the instrument so that you can call them up and get the scoop on their experiences with the system — from installation, to operation, to support. This is all very useful information when making your decision.

During the demo, you get a chance to look “under the hood” of the system. Find out which components are user-replaceable and which should only be changed by trained hands. A colleague of mine told me that his philosophy for instrument demonstration was to find a way to “break” the system and see how easy it was to troubleshoot and fix the issue. This may tell you more than if you were simply working on a fully functional system.

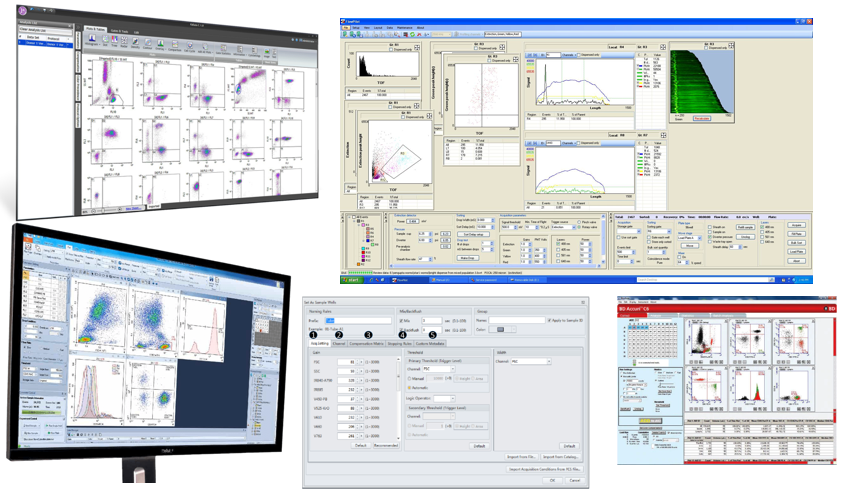

6. Did you evaluate the software?

Software represents the “brains” of the system, and it is critical to spend a lot of time focusing on this component. Poorly designed software can be highly detrimental to an otherwise excellent instrument. Review the software with an eye toward training people how to use it.

Another good thing to learn is how other software packages play with this instrument’s software. For example, is there any recommended anti-virus software that is better for the system? Likewise, how can access be controlled, or usage tracked? If your facility uses software like Stratocore’s PPMS or iLabs system for registration and tracking, does that cause any problems?

I have automatic data-backup software and a custom built QC program that has to access the instrument computers. When I was evaluating a certain instrument, the vendor indicated these could not be put onto their system. We ended up looking elsewhere because these were considered highly important for the operations we wanted to run.

Figure 4: Some common flow cytometry acquisition software. (Various sources)

7. What is the after-sale support like?

After-sale support is critical enough to be a deal-breaker. Once the bill is paid, that’s when support is needed. Support can be as simple as having seminars to promote the new system or having an applications team on-site for a few days to help train users on the software.

If the technology is significantly different from current technology, the education of operators and other researchers is essential. Since poor experimental planning yields poor data, make sure the best practices for the given technology are known. After-sale support is very important for new (and new-to-you) technology, so make sure it’s well-understood. Don’t be afraid to add specific clauses in your contract to address this.

At the end of the process, a shiny new instrument will arrive at your facility, complete with new-instrument smell. Make sure you find time to do a shakedown and validate the system. This is the time to get to know it better, identify quirks and potential issues, and develop training and QC programs. Once your shakedown is complete, you can start adding users and encouraging feedback on the system. Then, all that’s left is to enjoy your new tool.

To learn more about Ask These 7 Questions Before Purchasing A Flow Cytometer, and to get access to all of our advanced materials including 20 training videos, presentations, workbooks, and private group membership, get on the Flow Cytometry Mastery Class wait list.

ABOUT TIM BUSHNELL, PHD

Tim Bushnell holds a PhD in Biology from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He is a co-founder of—and didactic mind behind—ExCyte, the world’s leading flow cytometry training company, which organization boasts a veritable library of in-the-lab resources on sequencing, microscopy, and related topics in the life sciences.

More Written by Tim Bushnell, PhD